In dentistry as in medicine, you’ll find doctors on every side of contentious issues: is the mercury in amalgam dental fillings safe or not? (Yes, the science is clear that it’s safe). Is fluoride beneficial or dangerous? (Again, the science is solidly on the side of safety and efficacy). While dentists argue about which bonding agent or porcelain is best, one topic is almost guaranteed to cause huge fights: Occlusion and TMJ/TMD, if they’re connected or not, and even their basic definitions. If our profession can’t even agree, it’s not surprising that the public knows so little of what causes TMD, what can be done to treat it by dentists, when one should be evaluated or treated by other medical specialists, what medications help and which don’t. Hopefully this article helps clear up some of the myths & misinformation.

This article was co-written with Dr. Rich Hirschinger, an Orofacial Pain Specialist in California, and was first published in April 2017 in Massage & Fitness Magazine Winter 2017 edition.

“My Last Dentist Said I Have TMJ”

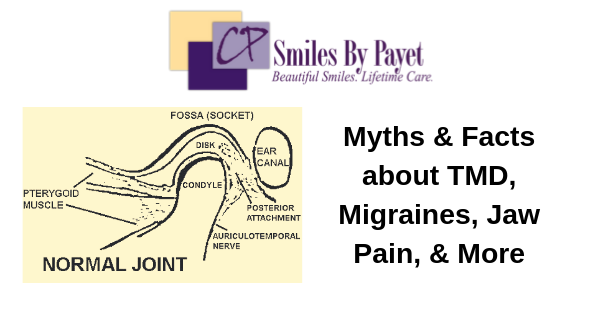

Whenever I hear this comment, I have to chuckle, because I sure hope they do! After all, “TMJ” simply means Temporomandibular Joint and refers to the joint where the uppermost part (the condyle) of your lower jaw (mandible) moves against the temporal bone at base of your skull. After all, you don’t go to the knee specialist and say, “I have knee.” What people really mean is that they have one or more signs and/or symptoms that fall under the broad term of Temporomandibular Disorders, or TMD. For most people, they think of these kinds of conditions:

- They clench or grind their teeth.

- They have pain in their jaw, likely due to muscle overuse.

- Their jaw makes some kind of noise when it opens and/or closes.

- They have difficulty opening their mouth wide, or perhaps it gets stuck (locked) open or closed at times.

The signs and symptoms of TMD, however, can encompass significantly more than these.

What Is TMD?

The first difficulty in discussing TMD is that there isn’t a universally agreed-upon definition, nor even what signs and symptoms are included. This is a point at which it’s worth reading the “Classification: Definitions and Terminology” section of the Wikipedia page on TMD(1) and at the NIDCR (2), as they illustrate many of the differences in terminology, symptom sets, etc. For this discussion, we’ll use the definition according to the International Association for the Study of Pain(3), because it is one of the most all-encompassing

Temporomandibular disorders (TMD) encompass a group of musculoskeletal and neuromuscular conditions that involve the temporomandibular joint (TMJ), the masticatory muscles, and all associated tissues. Pain associated with TMD can be clinically expressed as masticatory muscle pain (MMP) referred to as a myogenous temporomandibular disorder or TMJ pain (synovitis, capsulitis, osteoarthritis) referred to as an arthrogenous temporomandibular disorder. Chewing or other mandibular activity aggravates musculoskeletal pain. TMD pain can be (but is not necessarily) associated with biomechanical dysfunction of the temporomandibular joint (clicking or locking of the TMJ and limitation of jaw movement).

You’re probably more confused than before 😕 , so let’s break it down:

TMD includes a range of conditions that can involve any of the muscles, bones, connective tissue, and/or nerves associated with the TMJ. This includes all muscles that open or close the mandible or move it in any direction, the cartilage or synovial fluid in the joint space between the condyle and the skull, the mandible, and all the nerves involved in providing either sensation or movement to all the stuff I just listed. A quick summary of the anatomy:

- The Muscles of Mastication: superficial and deep masseters, lateral and medial pterygoids, and temporalis muscles.

- The Trigeminal Nerve (Cranial Nerve V), in particular the mandibular (V3) branch, which is a mixed nerve having both motor and sensory functions and innervates the muscles of mastication.

- The condyle, articular disk, and synovial fluid.

The signs and symptoms of TMD vary widely and can include any or all of the following:

- vague muscle aches to sharp muscle spasms in the shoulders, neck, head, and jaws

- joints that lock open or closed

- degeneration of the cartilage in the joint space, including arthritis

- popping, clicking, or grating (crepitus) of the joints on opening and/or closing

- sinus pain

- tension headaches and migraines

- condylar degeneration

- badly worn, cracked, and broken teeth or tooth pain

There are standards for research and diagnosis of TMD conditions (4), but this information is not widely known or understood within the medical and dental communities.

How Many People Suffer from TMD?

According to the IASP, 9-13% of the population suffers from TMD-related facial pain; among those, women represent at least a 2:1 majority, possibly up to 4:1. Onset is often in the teen years, peaks between 20-40 years old, and can last for an entire lifetime, but many people seem to “grow out of” their symptoms by their 40s or 50s. (5)

History of Thought on TMD Causes

In the good old days, by which I mean less than 20 years ago, almost all dentists were taught and believed that TMD was caused by grinding and/or clenching your teeth, which in turn was caused by malocclusion, aka a “bad bite.” Occlusion is the term for the relationship of the teeth when they come together. Therefore, malocclusion is any less than ideal fit of the teeth, while an ideal occlusion is generally defined as all teeth meeting with tripod contacts of cusps into the grooves of the opposing teeth in a Class I Angle’s Classification. (12) It was believed that any deviation from this ideal resulted in uneven forces on the contacting teeth, which would trigger muscle activity that would try to wear the teeth down until they fit more comfortably, even if they ended up looking like this:

Teeth damaged by grinding & clenching become short, chipped, worn, jagged, sharp, and ugly

Therefore, the solution to TMD was to simply fix the bad bite with either orthodontics, using the drill to adjust and reshape the teeth, or with dental crowns until they fit ideally. If only it were that easy!

Over the last two decades, it became apparent that malocclusion alone wasn’t enough.. We found that some people with a supposed “ideal” bite would still grind their teeth, while some people with even extreme non-ideal occlusal relationships did not. (6)(7) The paradigm shifted to “occluding” rather than occlusion; i.e. it wasn’t how the teeth fit together, but how the teeth come together during function. This began our understanding that TMD is really about parafunction, or abnormal function. (8) Further research has established that most parafunction occurs during certain stages of sleep. (9) Ongoing research is finding that various types of sleep disturbances, such as sleep-disordered breathing and sleep apnea, are significant risk factors for TMD, but we still don’t really know if they cause it. Sometimes, it is simply a case of a patient overusing the muscles of mastication during the day due to clenching their teeth or chewing gum.

However, many dentists still subscribe to the belief that poorly fitting teeth cause TMD, even though we know it’s not true. There is even a school of thought in dentistry called “neuromuscular dentistry,” which claims that fixing the bite can permanently cure chronic headaches, including migraines. They claim to do so by using a variety of computerized instruments to allegedly relax the jaw muscles and determine the “correct” jaw relationship. However, the evidence supporting the use of those instruments is weak and not to be trusted (10), and there are virtually no long-term studies of patients receiving NM dentistry to verify the claimed results.

Trauma, of course, can be a significant causal factor in TMD. Car accidents, fights, falls, etc. can all cause direct damage to the condyle or muscles via breaks, tears, and strains. Fortunately, TMD resulting from trauma can be the easiest to treat with palliative care and usually resolves on its own with time.

A common belief is that TMD is caused by “stress.” I imagine that massage therapists, in particular, hear their clients say, “Oh, my shoulders are tight because that’s where I carry my stress.” I hear it so often that I could retire early if I got a dollar every time. For a while, this belief was blindly accepted without any thought as to what that meant. Intriguingly, given what is now generally accepted as the Biopsychosocial Model of Pain (BSP), these people may have been closer than we guessed, but not for the reasons they believed. Of course, you can’t actually “carry” something as intangible as stress, but the shoulder and neck muscles can be triggered by muscle and nerve activity in the muscles of mastication, resulting in chronic, long-term tension.

All of the above possible causes, excepting trauma, fall into purely structural or functional models, however, and the research clearly indicates that alone is inadequate. The BSP, however, postulates, “…a biopsychosocial and multifactorial background, illustrating the complex interaction between biological (e.g., hormonal) mechanisms, psychological states and traits, environmental conditions, and macro- and micro-trauma.” (11) In other words, stress is a primary factor in TMD, but most people have a very limited idea of how many things constitute “stress.” Emotional, physical, hormonal, and environmental factors may all play a role, either individually or in combination, and they fluctuate over time.

How Do You Know if You Have TMD, & Who Diagnoses It?

In general, a diagnosis of TMD is made by taking a thorough history and clinical exam. Such an exam includes documenting the jaw’s range of motion, palpating the muscles of mastication, the neck, and shoulders, palpation and orthopedic manipulation of the TMJs, and a visual exam of the mouth that includes checking for tongue scalloping, cheek ridging and attrition, or wear from bruxism (grinding teeth). Range of motion is very important, and it can be obtained by using a range of motion scale. Opening measurements are comfort, active, and passive. Comfort is the patient’s comfortable opening without pain, Active is the patient’s maximum opening with pain, and passive is when the clinician stretches the patient open by placing their fingers on the upper and lower front teeth. Normal range of motion is between 40 mm and 60 mm.

While some groups claim that diagnostic imaging, such as MRIs, CT scans, panoramic x-rays, or an occlusal analysis via mounted study models of the teeth, or the use of electromyography is required, current evidence does not support their use. Diagnostic imagining will generally only appropriate to rule out pathology, such as tumors or damage by trauma. A sleep test may be recommended if there is evidence of sleep disordered breathing.

Even though tooth and jaw relationships are not likely causal factors in TMD, it is still true that the teeth often bear the brunt of joint, muscle, and nerve dysfunction in TMD. That’s why dentists often are the first professionals to diagnose TMD. Also, because most physicians (including specialists) generally know very little about TMD and dental conditions, they are less likely to look for the signs or symptoms that dentists see. It’s not uncommon for me to see patients who’ve already seen every specialist, had ever test or scan, and tried every medication without success, and no one ever suggested a dental exam. On the flip side, if a person has pain in the head or jaws that doesn’t seem to be directly related to the teeth, that person is likely to not discuss their symptoms with their dentist. The public often doesn’t see dentists as “real doctors who know about the whole head,” but only as “teeth and gum doctors.” Nevertheless, dentists are often the first to diagnose TMD symptoms, and often because of tooth wear and/or pain.

An important note: some dentists claim to be “TMJ specialists,” but the closest recognized specialty are those doctors who are Board-certified by the American Board of Orofacial Pain (ABOP). Most dentists who treat TMD, even oral surgeons, have generally studied the subject on their own and in post-graduate seminars. There are currently twelve post-graduate programs recognized by the Council on Dental Accreditation, which is affiliated with the American Dental Association, in orofacial pain in the USA and one in Canada, and those graduates who pass the ABOP exam are Board-certified, which is the closest one could claim to be a “TMD specialist.” As of early 2017, orofacial pain is a recognized specialty in only three US states, which are California, Florida, and Texas.

How is TMD Treated?

In general, TMD symptoms are treated with palliative care (11), such as jaw and neck stretching, NSAIDs, a nightguard, and rest. Assuming that one or more of the locations to which a patient is pointing is a muscle, usually one of the muscles of mastication, patients are advised that they fall into the “80/20 rule.” This means that we can help them but it is 80% up to them to follow the care plan. The following set of steps are recommended:

- They must learn to keep their teeth apart during the day using the “N rest” position, which is obtained by having the patient say the letter “N.” Their tongue should be on the roof of their mouth right behind the front teeth and their teeth should be apart. By keeping their teeth apart, the muscles of mastication are at rest. Keep in mind that the superficial masseter is the strongest muscle based on weight in the human body. (13)

- They need to stretch their jaw open to at least their active opening for 30 seconds about every two hours; while this usually causes pain, it is most likely stretching pain, which is good pain.

- They may need to adopt a soft diet for a period of time, and

- they should be wearing an appliance over their teeth during sleep.

There are a wide variety of nightguard designs; a discussion of them all is far beyond the scope of this discussion. Suffice it to say that, in the right patient, almost any of them can work, but in the wrong patient, some can cause significant damage or worsening of symptoms and may alter the jaw relationship, thus altering how the teeth fit together.

Muscle relaxants may be used on a short-term basis to treat acute pain, but they are not typically used as long-term therapy. Trigger point injections, dry needling, Botox and/or ligament injections can also be used, but who can provide these injections depends on individual state licensure boards.

Within the dental profession, neither massage therapy nor physical therapy are often recommended. This is primarily because there isn’t much research showing long-term benefit, and what there is, isn’t widely known. It is certainly true, however, that gentle stretching and/or massage of head, neck, and shoulder muscles may provide some pain relief, as well as decrease overall muscle tension. Cognitive Behavioral Therapy has also been shown to provide some relief. (14) Unless the patient consistently and regularly engages in such activities as part of an overall program to control nocturnal and/or diurnal parafunction, however, any benefits will be both minimal in nature and short-lived in duration. (15)

If you have TMJ/TMD problems, migraines, or other facial pain, you can

Request an Appointment Online or call us at 704-364-7069.

We’ll look forward to meeting you soon!

References

- Wikipedia https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Temporomandibular_joint_dysfunction

- NIDCR page on TMJ Disorders: https://www.nidcr.nih.gov/oralhealth/topics/tmj/tmjdisorders.htm

- IASP Fact Sheet on Temporomandibular Disorders http://iasp.files.cms-plus.com/Content/ContentFolders/GlobalYearAgainstPain2/20132014OrofacialPain/FactSheets/Temporomandibular_Disorders_2016.pdf

- Schiffman E, Ohrbach R, Truelove E, et al. Diagnostic Criteria for Temporomandibular Disorders (DC/TMD) for Clinical and Research Applications: Recommendations of the International RDC/TMD Consortium Network and Orofacial Pain Special Interest Group. Journal of oral & facial pain and headache. 2014;28(1):6-27.

- Manfredini D, Visscher CM, Guarda-Nardini L, Lobbezoo F. Occlusal factors are not related with self-reported bruxism. J Orofac Pain 2012;26:163–167.

- Michelotti A, Ciof I, Landino D, Galeone C, Farella M. Effects of experimental occlusal interferences in individuals reporting different levels of wake-time parafunctions. J Orofac Pain 2012;26:168–175.

- Glaros AG, Williams K. “Tooth contact” versus “clenching”: Oral parafunctions and facial pain. J Orofac Pain 2012; 26:176–180.

- Lavigne GJ, Kato T, Kolta A, Sessle BJ. Neurobiological mechanisms involved in sleep bruxism. Crit Rev Oral Biol Med 2003;14:30–46

- Manfredini D, Castroflorio T, Perinetti G, Guarda-Nardini L. Dental occlusion, body posture and temporomandibular disorders: where we are now and where we are heading for. J. Oral Rehab 2012; 39:463-471

- IASP Fact Sheet on Temporomandibular Disorders http://iasp.files.cms-plus.com/Content/ContentFolders/GlobalYearAgainstPain2/20132014OrofacialPain/FactSheets/Temporomandibular_Disorders_2016.pdf

- Dworkin SF, Turner JA, Mancl L, Wilson L, Massoth D, Huggins KH, LeResche L, Truelove E. A Randomized Clinical Trial of a Tailored Comprehensive Care Treatment Program for Temporomandibular Disorders. J Orofacial Pain 2002 Fall; 16(4):259-76

- Wikipedia https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Malocclusion#Classification

- Library of Congress https://www.loc.gov/rr/scitech/mysteries/muscles.html

- Turner JA, Mancl L, Aaron LA Short-and long-term efficacy of brief cognitive-behavioral therapy for patients with chronic temporomandibular disorder pain: A randomized, controlled trial. J Pain 2006 121:181-194

- Roldán-Barraza C, Janko S, Villanueva J, Araya I, Lauer HC. A systematic review and meta-analysis of usual treatment versus psychosocial interventions in the treatment of myofascial temporomandibular disorder pain. J Oral Facial Pain Headache.2014 Summer;28(3):205-22. doi: 10.11607/ofph.1241